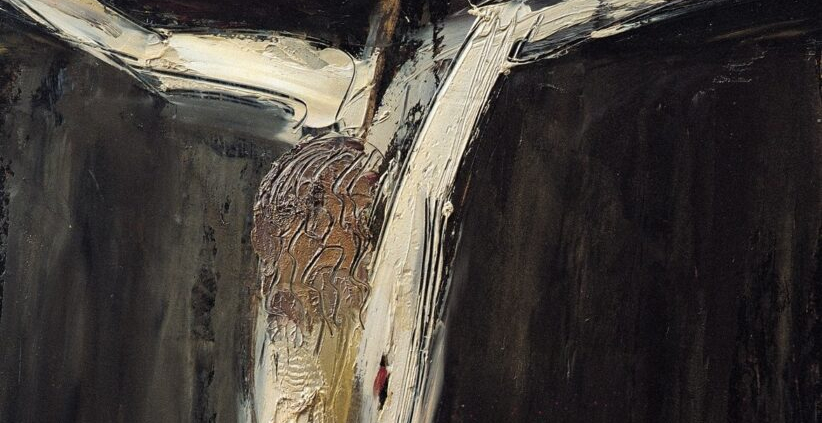

Action Painting in a Lombard farmhouse

2021 concluded, for Galactus Translations, with the translation of a a number of essays on the painter William Congdon (1912-1998). This project has enabled us to deepen our awareness of an American artist who made Italy his second home. We thank Casa Testori for this opportunity and, in particular, Davide Dall’Ombra and Giuseppe Frangi, from whose essays we have drawn the information you will read in this brief introduction.

William Grosvenor Congdon was born in Providence, on Rhode Island, in 1912, the same night as the sinking of the Titanic, a coincidence that was fundamental for the formation of his stock of imagery. He discovered his vocation when faced with the horrors of the Second World War, of which he was a direct witness, having been enrolled in the rescue structure of the American Field Service. His first drawings were documents of the war and of the Bergen Belsen concentration camp, where he took part in its dramatic dismantling. In 1948-1950 he became a full time painter and adhered to the New York experience of Action Painting, exhibiting several times in the reference gallery of the group, the Betty Parson Gallery.

From US to Lombardy (Italy)

In the 1950s, however, he left the USA more and more frequently. He spent long periods in Venice, where he frequented the circle of Peggy Guggenheim. His long stays in Italy, his country of adoption from the 1950s, were characterized by his enchantment with the beauty of the historical cities, Venice before all, but Congdon injected a destructive energy in his views of the buildings, squares and monuments. The buildings on the Canal Grande seem disrupted by a wind that shakes them, the Colosseum, with its enclosure precipitating into a dark whirlpool, seems to collapse upon itself. We recognize the leitmotif of an implacable disquiet in Congdon during those years. A disquiet that led him to explore the frontiers of the world, from India to Africa, to participate with his paintings in the spasms of the earth. As he confesses in his diaries, those worlds belonged to him because he found there an absolute lack of the “ego” which dominated the West and his own America in particular.

The Milanese countryside

In every one of the paintings from this period, we may capture an undertow, as if painting was equivalent to the pains of labour. Congdon’s painting is always in search of “something else”, in the words of another similarly unquiet artist of those years, Mario Schifano. Seeking the experience of a new birth may give a sense and a name to that unstanchable wound. The key moment was his conversion in 1959. But it was above all from his arrival, in October 1979, in his studio in the Milanese hinterland, that Congdon’s art opened to a new vision. “I must rewrite my entire story, updating it in this new land”, he wrote in his diary on 21st October 1979. “This must be my port of arrival, that is to say the promised land”. The silence of the fields and of the nearby Benedictine monastery became a point of new departure. A silence that recreated his painting, transforming it into repeated and daily pictorial gestures of obedience. It was the design of the fields that suggested to him new visions and new solutions, in the guise of a sequel.

Silence in the fields

The paintings almost become camouflaged surfaces of the geometrical forms of the fields. But this is not just the result of aesthetic fascination: Congdon sets his painting out in an attitude of waiting, as if the canvases were fertile ground for a miracle that is about to renew itself and take place, exactly as happens with nature every spring. The ancient wound becomes, in the end, an opening from which filters a light that is ever new. Here he remained throughout his last years, till his death on 15th April 1998.

Until 27th March 2022 you can visit the exhibition “William Congdon. 30 dipinti dalla William G. Congdon Foundation” at Palazzo Bisaccioni, Jesi (Ancona, Italy).

For more information you can visit the William Congdon Foundation, Buccinasco (Milan, Italy).

Image: Artslife.com

William Congdon Foundation

William Congdon Foundation

Collins

Collins