Italian Carabinieri to be eliminated

A strong title, but one that hits the mark. The Appuntato Scelto Q.S. [Lance Corporal] Enrico Cursi chose it for the book he wrote and published in 2018 (Ed. Chillemi). We had the pleasure to interview the author during an archive research Galactus Translations conducted for one of its clients. The support and clarifications provided by Enrico on the events involving the Carabinieri during the Second World War were of great help to us. We are profoundly grateful for the time he dedicated to us and for his contribution to an increased awareness of historical events that would otherwise have remained locked away in a file and forgotten.

Why were some Carabinieri “to be eliminated”? And why only in the period 8th September to 7th October 1943?

On 25th July 1943 the Arma dei Carabinieri Reali was appointed to “arrest” Mussolini. The Duce was picked up and taken to the Legione Allievi Carabinieri di Roma for subsequent transferral to other secret destinations. Even though no report exists of the arrest of the Duce, the operation was conducted as a real capture. The Carabinieri, as was known at the time, were monarchists and were therefore, for the Fascists and Nazis, an extraneous and unreliable body to be “eliminated”. After the Armistice in Rome, and in other Italian cities too, the Carabinieri fought against the German dominance.

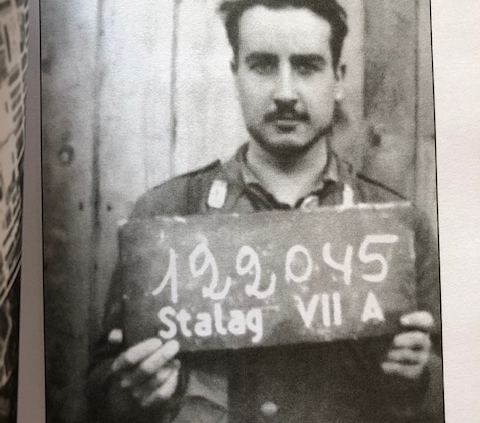

Can you explain us the photo on the cover? Who is it?

During my research, I principally consulted the archives of the Ufficio Storico del Comando Generale dell’Arma dei Carabinieri. I also had contacts with the Associazione Nazionale Reduci dalla Prigionia (ANRP). In these archives in Rome, I found photos of Carabinieri interned in German concentration camps. The photo on the cover of the book was chosen for two reasons. In the first place, it shows the moment of entry to the camp. The Carabiniero, in fact, has a ring, long hair and his uniform in order. The second reason, which prevailed, is that I was struck by the look on the non-commissioned officer’s face. The life of this young man, his surname was Nardone, was to be cut short in 1944 by allied bombing. Every time I pick up this photo, the look on this young man’s face still moves me strongly.

Why did you decide to write this book?

I’ll be very sincere. Everything began when I came across the letter signed by General Graziano, ordering the Carabinieri of Rome to disarm. I had never seen or heard anything about this episode, which took place on 7th October 1943. I immediately asked myself several questions, which I was unable to answer. I therefore began the research that led to this book.

Did you interview any relatives of the eliminated Carabinieri? What effect did meeting them have on you?

I’m glad you asked me this. One of the things that I believe fundamental for historical research is the testimonies of survivors or of people who lived through the period. During my research, I was fortunate to meet several relatives and deportees who, with great generosity, welcomed me to their homes and told me their stories, often with strong emotions. I’m profoundly grateful to these people, not least because I realize I was reopening painful wounds.

Why do you speak only of Rome?

The deportation of 7th October 1943 concerned only the Carabinieri of the capital. There were other deportations involving Carabinieri during the war, but that of Rome was complex in its methods, which I try to relate in my book. Another fact worth remembering is that the Arma dei Carabinieri, in that historical moment, was divided. There was one institution in the territories held by the Nazi-Fascists, headed by General Mischi, and another in the liberated sectors of southern Italy was commanded by General Pieche.

On what are you concentrating your research at the moment?

At the moment, I am working on two projects concerning the resistance in Tuscany in 1943 and 1944. The first episode is the story of a Carabiniero who offered his life to save those of others, while the other tells of a group of patriots, consisting of Carabinieri, which worked to free Florence.

You are first of all a Carabiniero. Was it difficult set about writing a book?

This is my second book and I wrote it with great enthusiasm. As with everything we love, doing the research and writing the text was above all something I needed to do. Since I am not a writer by profession, I am conscious of my limits. My research was inevitably affected by my professional engagements, but this was not a problem. Indeed, there were times when the pauses helped me to reflect and reason.

Did you feel emotionally involved while you were writing the book or during the research phase?

I certainly did. I confess to you that at times, if I am in a railway station and see a goods train pass, I think of the transfer of those 2,000 Carabinieri from Rome to the three detention camps. For a few moments, I try to imagine how those men must have felt during their transfer to the lagers. The suffocating heat due to the large number of occupants, their hunger, their thirst, their grief for not having been able to say farewell to their loved ones and, worse still, for not having been able to leave any information about their real destiny and place of arrival.

What can the reader learn from this book?

This book was conceived to remember an event that is still little known. I hope that this research may be useful to other researchers and keep alive the memory of those Carabinieri who sacrificed their lives for our freedom.

All the staff of Galactus extend their heartfelt thanks to Enrico Cursi.

William Congdon Foundation

William Congdon Foundation